Designing behavior.

It’s the goal of good design and yet so much more than that.

Because behavior is everything. Every action you take. Every action you want others to take: employees, customers, your family.

If you’re a business or marketing leader, behavior design has everything to do with your roles in work and life as someone who grows and succeeds and helps others do the same.

BJ Fogg’s Behavior Model is a way to better understand behavior—or lack of it—so you can change or encourage it.

Whether you want your customers to take action.

Whether you want to overcome your habits to build new ones.

Whether you want your employees to perform or take change well.

You can observe anything and anyone that can behave through the Fogg Behavior Model to guide behavior change.

What Is the Fogg Behavior Model: A Quick Rundown

The behavior model was invented by Dr. BJ Fogg, the Behavior Scientist behind the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University and the book “Tiny Habits: The Small Changes that Change Everything.”

The Fogg Behavior Model is based on the fundamental idea that behavior (B) occurs when three things align: motivation (M), ability (A), and prompt (P). If one of these is missing, then the behavior you want won’t occur.

You can sum up the model with the equation B=MAP, though it’s easiest to understand using the Fogg Behavior Model chart below.

Why Have I Seen B=MAT?

If you’ve seen the equation with a T instead of a P, it’s because BJ Fogg originally used the word Triggers instead of Prompts. The terms are basically interchangeable, but Prompt became the official term in 2017.

How the Fogg Behavior Model Works

Looking at the Fogg Model:

- Motivation (the why of an action) lives on a vertical axis

- Ability (the how of an action) lives on the horizontal axis

- The Action Line shows where action takes place.

- Above the line is where a prompt succeeds because motivation is high enough and/or ability easy enough.

- Below the line is where a prompt fails because motivation or ability is too low.

That’s the simple explanation.

Now for the nitty-gritty of each element.

Motivation

Motivation ranges from low to high, but you know what it’s like to be motivated and unmotivated to do something.

Motivation is generally the most critical factor in moving behavior but is also the hardest to change and rely on.

That’s why the greatest success is found in uncovering what motivation(s) already exist.

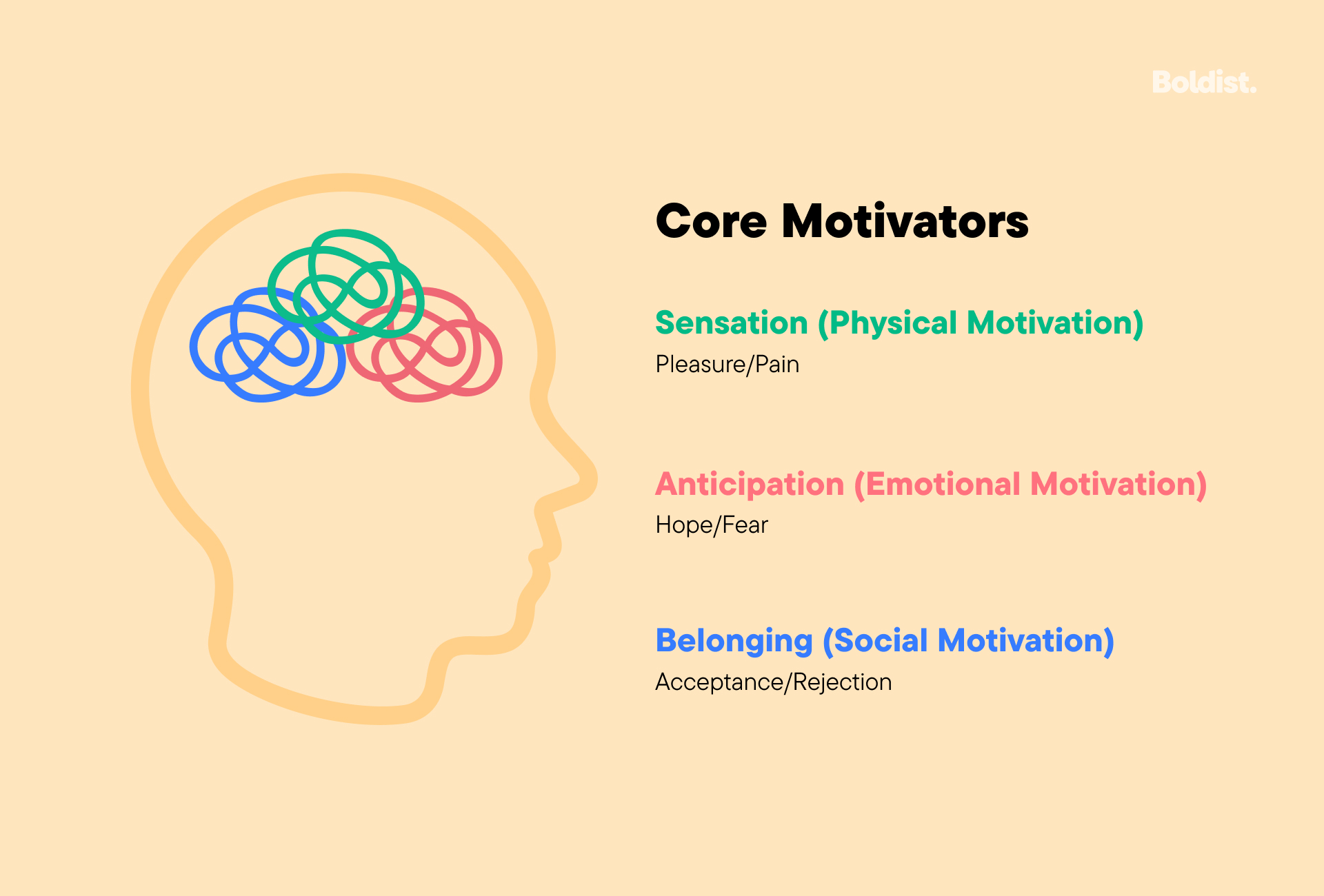

You can categorize motivations into 3 dual-sided “core motivators.”

1. Sensation (Physical Motivation)

Pleasure/Pain

People naturally try to avoid pain and gain pleasure. It’s really that simple.

2. Anticipation (Emotional Motivation)

Hope/Fear

We prefer hope, but fear of the worst can be equally powerful (it’s why people buy insurance). Just keep in mind ethics when dealing with fear.

This future-focused core motivator is also associated with purpose in an existential sense.

3. Belonging (Social Motivation)

Acceptance/Rejection

This is where community comes in. We’re social creatures, after all.

Ability

Ability refers to one’s ability to do something, ranging from easy to hard.

Actions need to feel attainable. The easier success is to picture, the better.

The harder something is to do, the more motivation you need. The easier it is, the less motivation you need.

Ability is not competence.

Rather, it’s how easy it is for one to do a task at a particular moment in time.

There are 3 ways to increase ability:

1. Training: This is the hardest method and only recommended if required, especially in the case of customer behavior. Most people don’t want training; they want things to be intuitive.

2. Tools: Tools exist solely to make tasks easier.

3. Simplicity: Simplify the steps to the behavior you want. Make practice sessions shorter; reduce the number of questions in your survey; require fewer clicks to finalize a purchase. In our field, this is all about removing friction.

Simplicity Is the Best Way to Impact Ability

BJ Fogg says that simplicity is the best way to improve ability, and in our experience, we agree.

If someone isn’t motivated enough to take action, starting small or making the task easier will increase the likelihood that they’ll do it. If it takes little effort, one finds themself thinking, “Why not?”

And in most cases, simplifying a task is much easier than creating motivation.

Then, by experiencing the benefits of small steps, motivation may build. So even as a task becomes harder, motivation can increase to keep them above the action line.

A great insight from BJ Fogg is that:

“Simplicity is a function of your scarcest resource at that moment.”

There are 5 potentially scarce resources to be aware of when creating ability:

- Time

- Money

- Physical Effort

- Mental Effort

- Routine

If you’re unsure how to simplify a desired behavior, look at which factor is scarcest at the time of your prompt. How can you reduce it or address it at that moment?

These resources also show why ability and competency are different. For instance:

- A task might take a mere 5 minutes, but if I only have 5 minutes of free time, you’re now asking a lot.

- You can be competent, but if you’re burnt out at the moment, a task you’re capable of becomes significantly harder to do.

When it comes to mental effort in particular, it’s easy to assume ability is easier than it is.

A person makes 35,000 decisions a day on average, from the near-subconscious to those that require noticeable effort. Adding to that mental load can quickly lead to fatigue and postponement.

It’s why—in our industry—simplification of user flow is critical to conversion optimization.

High motivation but unnecessarily hard ability is where missed opportunities pile up. People can’t do what they want to do, creating frustration (or what we call friction).

Understanding Routine as an Ability Factor

Routine is the most unusual ability factor of the five listed but just as vital as the ones we’re more familiar with—like time or money.

If a task doesn’t fit into one’s routine, it becomes challenging and uncomfortable.

Let’s go back to the incredible number of decisions a person makes daily. Many of these decisions are made easier through habit or “routine.”

As a result, routines reduce overload and stress.

Minor changes to routine add up and can even begin to feel threatening. So, the response is generally negative when you put undue stress on one’s routine or push them where ability is out of range.

Prompts

Prompts prompt behavior. They may be cues, triggers, calls to action, requests, or offers.

If someone is highly motivated and the task is super easy, they still may not do it without a prompt to trigger the action.

A prompt can be an external request or reminder from people, notifications, or the environment (digital environments included) or an internal cue from a physical response or routine.

There are 3 types of prompt.

1. Facilitator: For motivated individuals, facilitators prompt the behavior and contribute to ability—say, by walking the individual through the steps.

2. Spark: For those with ability, sparks prompt the behavior while “sparking” motivation. You want to be careful with sparks; if they fail, you may annoy people lacking the intent you need.

3. Signal: Signals are a sign or reminder for those who already have ability and motivation.

In writing or structuring your prompts, always consider whose behavior you want to change and whether they need help with motivation, ability, or recall.

Timing: Why MAP Has to Be “At the Same Moment”

For behavior change to succeed, you need motivation, ability, and prompt simultaneously.

It won’t do any good if I’m no longer motivated by the time I have the ability. It won’t do any good if a prompt is given when I’m not currently able.

Timing can be the trickiest element to master, especially in sales.

If you give me a pop-up when I’m trying to do something else (not motivated), I will be annoyed. If you ask too much of me when I’m trying to purchase a product, I might get frustrated.

A great example of the importance of “the right prompt at the right time” is the $300-million-dollar button: a case study where changing one button (and yes, a button is a prompt) made a company $300,000,000.

The company required users to fill out a form before checking out.

It was a simple username and password form. It had the buttons “login” and “register.”

The problem?

Many potential customers bounced because they couldn’t remember their login or if they already had an account (ability). Others left because they didn’t want to create an account (motivation).

In the end, replacing the “Register” button with the option to simply “Continue” was all it took to, well, get buyers to continue.

(If you’re wondering, they gave the option to create an account later during checkout.)

The Fogg Behavioral Model in Action

For fun, let’s look at a couple of simple Fogg Behavior Model examples.

Example 1: Getting Visitors to Subscribe to a Company Newsletter

- Low motivation: A website visitor sees the call to action to sign up for the company’s newsletter. They have the time to sign up for the newsletter and to read it when it comes out every Friday. However, they don’t know what the newsletter is about or how reading it will benefit them.

- Low ability: A site visitor gets a pop-up asking them to sign up for the company’s newsletter. It convinces them why they should sign up, but the form asks 10 questions about subscriber preferences and personal information, so they give up.

- Lacking prompt: A visitor loves the blog article they just read on a company’s website. They’d be willing and able to sign up for a newsletter with more content like it, but they don’t know the company has a newsletter.

Example 2: Building a Habit to Meditate Daily

- Low motivation: You downloaded a meditation app your friend recommended in a passing conversation. The app sends you a notification to do your daily meditation, but you’d rather watch the next episode of the show you’re watching.

- Low ability: You read an article on how good meditation is for you, so you add meditating for 10 minutes to your morning to-do list. However, when you try, you can’t keep still or figure out how to clear your thoughts. After 3 minutes, you give up.

- Lacking prompt: You read an article on how good meditation is for you, so you download an app with 3-minute beginner videos. However, you don’t allow notifications, so you don’t receive the app’s reminders and forget. Alternatively, the app doesn’t let you set when to remind you, so it always notifies you when you’re busy.

How to Influence Behavior Change with Fogg’s Model

Tactics for Increasing Motivation

Here’s a list of example tactics that target the core motivators of sensation, anticipation, and belonging.

- Gamify tasks

- Use levels to track progress

- Celebrate achievements

- Use limited offers to create scarcity

- Address cognitive dissonance

- Use storytelling

- Create curiosity

- Put a date on results to bring the future into sight

- Provide social proof

- Appeal to status and reputation

- Give freely to encourage reciprocation (When someone gives you a gift on your birthday, you feel obligated to do the same on theirs.)

Other strategies include Loss Aversion and Sunk Cost, but we consider these negative strategies unless you’re using them to your advantage by recognizing them as fallacies.

Tactics for Increasing Ability

Here’s a list of example tactics for simplifying tasks and easing ability.

- Break tasks into more manageable parts

- Remove distractions to encourage tunneling

- List steps to encourage tunneling

- Prioritize, segment, and personalize to reduce the amount of information to sift through

- Chunk alike information together

- Simplify comprehension and recall by linking new ideas to familiar concepts

- Limit options to simplify decision-making

- Provide readily available help and support

- Remove all guesswork about what needs to be done

- Remove all guesswork as to what to expect

- Make it mobile (The ability to do tasks on the phone, where people already spend a lot of time, is an example of making a behavior routine-friendly.)

- Use or provide automation tools

- Identify all physical steps you can remove or simplify

- Follow accessibility guidelines

Tactics for Improving Prompts

Here are some tips to use when creating prompts.

- Never rely on recall

- Uncover the optimal time for the prompt to trigger

- Ensure the prompt is noticeable

- Use recurring prompts to build routine

- Engage with the fresh start effect (e.g., New Year’s Eve resolutions)

- Avoid requiring resources that might not be readily available

- Keep prompts simple

- Opt for one small prompt at a time over multiple asks all at once

- Prompts on cell phones are hard to miss

- Emails and SMS are great prompting tools for ecommerce

Break Behaviors Down

Significant changes are often made up of smaller actions and choices.

While you can use the behavioral model to generally understand large-scale behavior, like why someone makes a purchase or to address long-term shifts like employee burnout, it’s most valuable when you apply it to the steps or actions that make up that behavior.

Tap Into Existing Motivation

You can’t create motivation where it doesn’t exist. Or, at least, it isn’t easy.

What you’re trying to motivate a person to do needs to match what they already want on some fundamental level.

When you realize your first goal is to understand what motivation already exists to tap into, working with motivation becomes much easier, whether for converting buyers or practicing your own discipline.

Work With Competing Motivations

A person can have competing motivations at any given time.

To quit smoking may be more socially acceptable, but smoking itself may be pleasurable, especially compared to the pain of quitting an addiction.

Exercise can be uncomfortable, but post-exercise endorphins can be pleasant.

Listing the other motivations that can and will compete with your desired behavior is the first step to preventing them from getting in your way.

But it won’t always be about fighting them. You may:

- Decide how to remove the conflicting motivation or make your primary motivation stronger than it is.

- Decide that you can find a way to balance both motivations if balance is a better choice in the situation.

- Decide to create space when other motivations align more strongly with your values.

To give an example of the latter: If you wanted to exercise today, but a family member needed you, you can create the understanding that it’s okay to miss a day to help them, so you don’t suffer from guilt or judgment that you strayed from your initial goal.

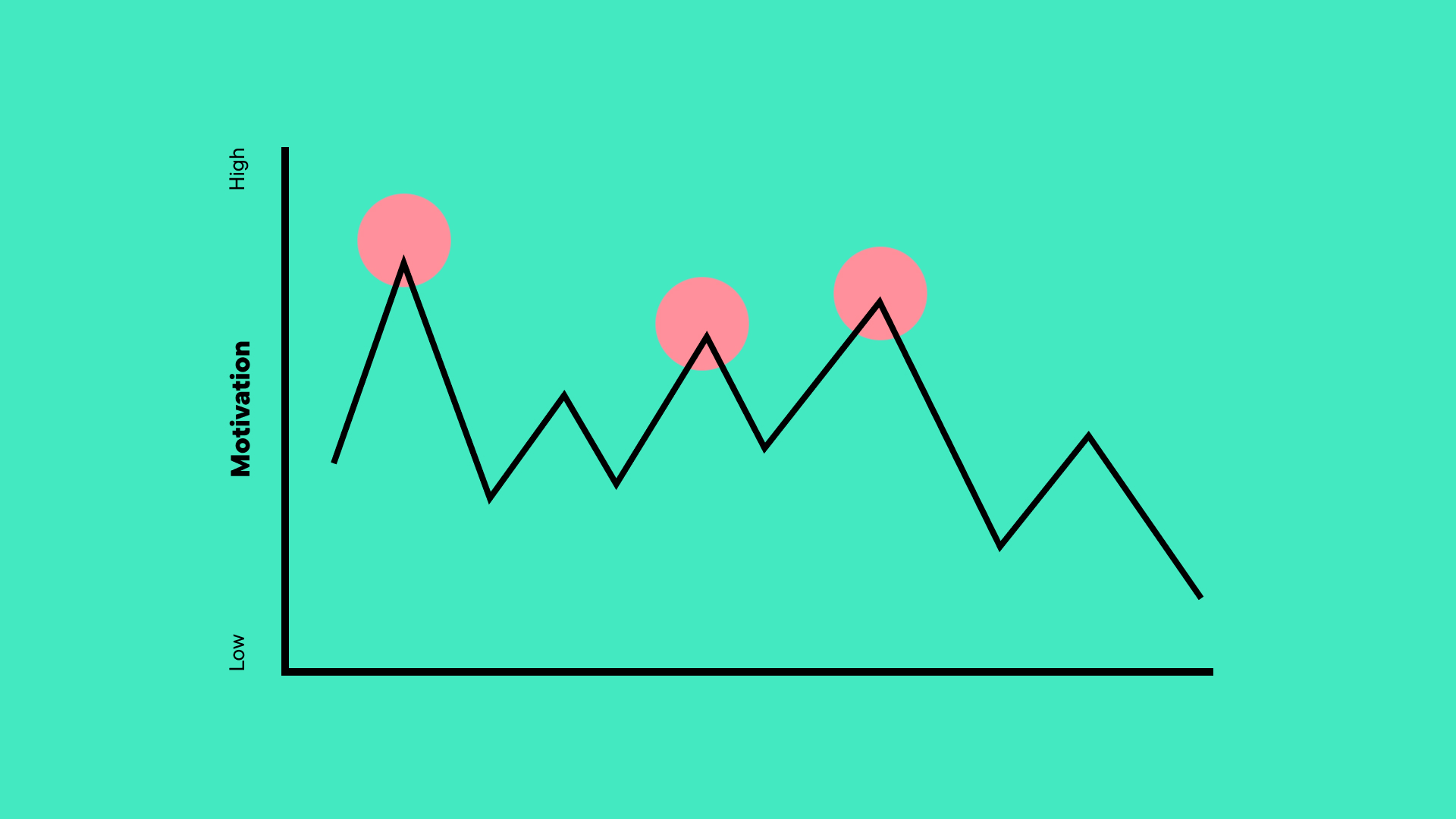

Take Advantage of Motivation Waves

BJ Fogg also talks about motivation waves: times in our life when motivation spikes and we’re willing to do things that require more effort.

Motivation waves can be recurring or one-off instances.

For instance, you may find that you’re consistently more motivated to meditate first thing in the morning, but by evening, you’ve lost that will.

You may also find that watching the Olympics encourages you to get in shape or that hearing about an oncoming storm encourages you to fix your broken window screens.

But like a wave, these spikes fall.

Your goal is to identify or predict potential peaks and get the behavior to occur within them—or ensure the behavior becomes more accessible or desired by the time motivation dips.

Picking Your “Audience”

Sometimes you already know who you’re working with. Other times you may still need to pick or shift.

You can tap into the motivations people already have, but you can also tap into those with the motivation and ability to meet your desired behavior:

- The segment that has a genuine desire for your product

- The employee with motivations that set them up to thrive in your office culture

- The partner with the same motivations in a relationship

- And so on

Yeah, you can make your product cheaper to appeal to money-related scarcity. But maybe you need to target those who buy luxury goods.

Additionally, some audiences will trade one resource for another:

People partake in physical labor in exchange for money. People with money spend it on tools that save them time.

You might also ask yourself if a larger audience is a better audience. What’s valuable changes with the goal and context:

You can get a few people to donate $100, or you can set the donation minimum to $5 and get way more donations, though in smaller amounts. You can make an application short to get more applicants or make it more challenging to get a more qualified few.

Ability in Environments

Environments, physical and digital, play an essential role in ability.

You may find a messy home hard to think in. A prison cell doesn’t make for a stimulating office.

Being who we are, we have to take a second to talk about user interfaces.

It doesn’t matter if a user is motivated and able if the interface isn’t intuitive. They can have all the cause, time, and money in the world, but if they can’t figure out where to go, find what they’re looking for, or understand an error message that appears, they’ll give up.

And fun design can be fun. But if it’s too unfamiliar, you enter the realm of the non-routine, where “unique” is hard to use and goals die.

As Always, Test

It doesn’t matter if you’re working on yourself or conversion rate optimization: You can always test!

Use the Fogg Behavioral Model to identify areas and possibilities to test in an organized fashion. Where can you improve ability, motivation, or prompt? Which one has the greatest effect on that goal? The next one?

Run personal experiments and grand ones.

Let us know how it goes.